Lost and Found

by Oliver Jeffers

New York: The Penguin Group, 2005.

Suggested Grade and Interest Level: Pre-K through 2

Other languages: Spanish (perdido y encontrado); French: (perdu retrouve); Catalan, Chinese, Danish, Finnish, Gaelic, Galician, German, Greek, Hebrew, Hungarian, Italian, Japanese, Norwegian, Persian, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Swedish, Turkish, and Vietnamese

Awards: Nestlé Smarties Book Prize Gold Award, Blue Peter Book of the Year

Other media: Lost and Found, the animated film produced for TV, narrated by Jim Broadbent, Winner of BAFTA award (British Academy Films Award) along with over 40 international awards, available on Amazon Prime; book is also available in ebook and Kindle editions.

Topics to Explore: Birds, Penguins; Feelings; Friendship; Geography, South Pole; Imagination; Kindness and Empathy; Perspective-taking; Shadows and reflections

Skills to Build:

Concepts of print

Vocabulary: Synonyms, Antonyms, Adjectives, Similes, Prepositions

Beginning concepts: Sizes, colors, and shapes; Part-Whole relationships

Grammar and syntax: Early utterances, Noun-verb agreement, Present progressive and past tenses, Negative structures, Advanced syntactic structures

Language literacy (a.k.a. Language discourse): Predicting, Problem Solving, Sequencing events, Cause-and-effect relationships, Storytelling, Drawing inferences, Point of View, Verbal expression, Giving explanations, Discussion, Answering Why-questions

Social pragmatics: Being a friend, Conversational skills, Non-verbal communication

Executive functioning: Planning and organizing, Flexibility

Articulation – P, B, and L

Fluency

Summary: When a penguin shows up at a boy’s doorstep in a charming little seaside town, the bewildered boy must think of what to do. The sad looking penguin follows him everywhere, and the kindhearted boy believes it to be lost. But the Lost and Found Office doesn’t know what do to, and his feathered friends at the park and bathtub ducky don’t know either. Then he discovers by reading his big red book that penguins come from the South Pole. So, he makes his little rowboat seaworthy and rows the penguin across the high seas back to its faraway home. On their journey they experience each other’s companionship. Then, after the boy drops it off and rows away, he has second thoughts. Oh no! A mistake! The penguin wasn’t lost! It was lonely! He turns the boat around and just misses the penguin behind an iceberg, as it has already left the South Pole. All ends well as they eventually reunite, and their sweet embrace will warm your heart.

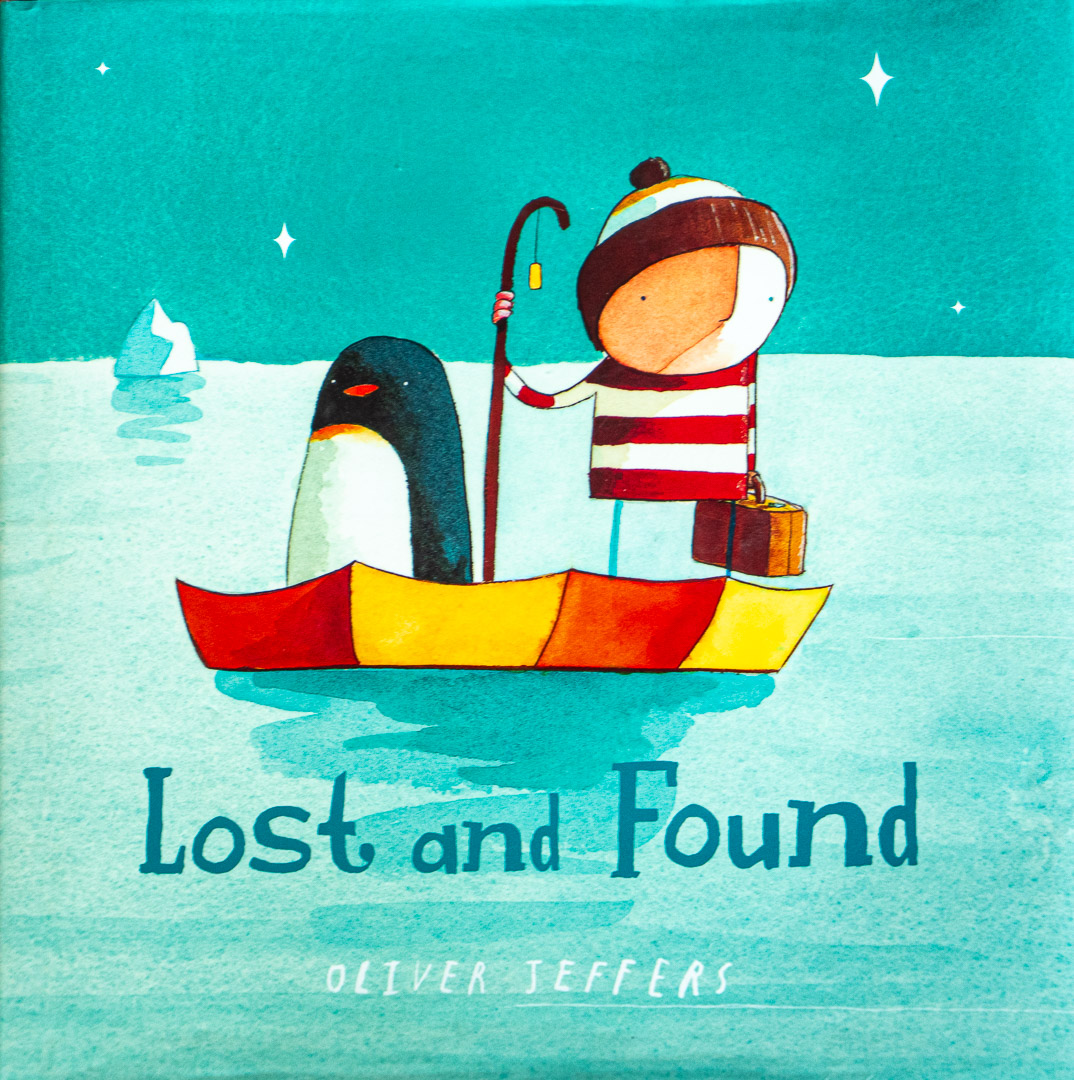

Methods: Before the read-aloud, as you introduce the book, show the cover with the boy and penguin inside an upside down umbrella floating on the icy waters of a polar region. Encourage children to share what they know about a happy topic – penguins! Start a discussion with questions such as –

- What makes them interesting? (E.g., they’re black and white, flightless birds, waddle, seen in movies, on so on)

- Where do they come from?

Vocabulary, Beginning Concepts

To work on colors, shapes, and sizes, encourage picture descriptions of the cover image. The simple watercolor drawings in vibrant colors make labeling and describing the boy, penguin, water, and “boat” easy and fun.

To work on part-whole relationships, identify what the boy and penguin are riding in. The top part of the umbrella is upside down and submerged in the water, so recognizing the whole object may require some descriptions and naming of features (such as the handle). Some suggestions –

- Is it right-side up or upside down?

- What is that object in the center that the boy is holding?

- When would you usually use this object?

Then set the stage for one of the story’s locations by sharing descriptions of the sea, the iceberg in the distance, and the shape of the stars in the sky.

Concepts of print

To work on print awareness, show the book’s title on the cover, running your finger beneath the words in the direction in which they are read. Ask children to read it with you. Encourage them to be on the lookout for the same words that will appear again in the story.

On a page turn, see the title page and ask children to read the title with you, as they’ve just read it on the cover. Build print awareness by saying that the words will appear again in the story and to be on the lookout for them.

Predicting events

Encourage predictions about how the boy and penguin might come to be connected in the story. Build anticipation as you read the title.

Continue to encourage predictions about what might happen in the story based on the cover. Draw connections between the cover images and the words of the title. For example, you might ask –

- What does the boy have in his hand?

- When does someone use a suitcase?

- What does a suitcase and Lost and Found tell us about what might happen in this story?

Vocabulary, Grammar and Syntax

On the title page, re-read the book’s title. Encourage picture descriptions as you support grammar and syntax constructions, from early utterances, to noun+verb agreement, to complex sentence formations. Some suggestions –

- Sun sets

- Long shadows

- Go for a walk

- Boy and penguin walk

- The boy and penguin go for a walk.

- As the sun reflects on the water, the boy and penguin go for a walk.

Enhance vocabulary development while eliciting target structures by asking questions such as –

- What are the dark shapes called on the path in front of them? (Shadows)

- What is the shining shape on the water beneath the sun called? (Reflection)

Then encourage use of the word within the story’s context as you scaffold ways to connect the new word to other words about the story for contextualized learning. Some suggestions –

- The boy sees his shadow on the ground in front of him.

- The sun is low in the sky. It casts a long shadow in front of the boy.

- The little penguin’s shadow is next to the boy’s.

- The sun’s reflection shimmers on the water.

During the read-aloud, continue to involve children in the language of the story by modeling a response, shaping a target structure, or expanding an utterance to connect more words to their meaning.

Problem solving, More Vocabulary, Beginning concepts

On the first two page turns, as the penguin comes to the boy’s door, work on problem solving by asking children to state the problem in the story. For example, you might ask –

- What might the boy be thinking about the penguin that arrived on his doorstep?

- What does the penguin’s expression tell you about how it feels?

- What is the problem the boy wants to solve?

Continue to target vocabulary in talking about the shadows cast on the ground from the two figures.

- Are the shadows short or long?

- Are they longer than when you saw them on the first page?

- Do shadows change shape? Why do you think so?

Work on prepositions in front and behind by using the illustration accompanied by text that states –

The boy didn’t know where it had come from,

but it began to follow him everywhere.

Ask questions such as –

- Where is the penguin? (behind the boy)

- When someone follows someone or something, where are they? (behind, in back of)

- Where is the penguin in this picture? (behind the boy)

Concepts of Print, Giving explanations

On the next page turn, see the boy trying to solve the penguin’s problem by taking it to the Lost and Found Office.

To continue work on print awareness , point to the writing on the desk that reads Lost and Found. While the font has changed from that of the title, the words remain the same. After reading them, prompt with questions such as –

- Where else have we seen those words?

To encourage verbal explanations about why the Lost and Found Office might not apply to a penguin being lost, consider asking questions such as –

- If the penguin were lost, would you try to find its home by going to the Lost and Found?

- Why not?

- What do you usually find at the Lost and Found?

Pragmatic language

To work on nonverbal communication skills, point out the boy’s expression and body language as he tries to explain to the man at the Lost and Found desk about the penguin at his side. Then read the man’s expression. Prompts might include –

- What does the boy’s outstretched hand indicate he might be saying?

- How would he likely ask a question of the man at the desk?

- What does the man’s expression tell us about his response?

More Vocabulary, Synonyms, Grammar and Syntax

On the next few page turns, see the boy still trying to solve the lost penguin’s problem without success. Target grammar and syntax constructions, including negative structures, by modeling a response, shaping a target structure, and/or expanding on an utterance. Some examples include –

- The birds didn’t know (where the penguin came from).

- His bathtub ducky didn’t know (where penguin came from).

- The people on the big ship couldn’t hear him.

- The boy couldn’t sleep.

- He didn’t know how to help (the penguin).

To work on vocabulary, talk about the boy’s efforts to help the sad little penguin, and his response when he can’t seem to solve the problem.

The story reads –

That night, the boy couldn’t sleep for disappointment. He wanted to help the penguin, but he isn’t sure how.

Ask questions such as –

- Why couldn’t the boy sleep that night? (E.g., He was feeling sad, frustrated, disappointed, worried)

- What are some ways to describe how he feels?

Then encourage use of the word disappointed as you scaffold ways to connect it to other words about the story for contextualized learning. Some suggestions –

- The boy was disappointed that he couldn’t help the penguin.

- The boy was disappointed that he couldn’t find a way to get the penguin back to its home.

To work on synonyms, brainstorm other words for disappointed. Some suggestions –

- discouraged

- dismayed

- sad

- let down

- worried

- bewildered

Cause and Effect Relationships

On the next few page turns, the boy decides to take the penguin back to the South Pole, where he believes it wants to return home. See him testing out his boat, packing his suitcase (including the umbrella), and preparing for their adventurous row.

Support children in expressing cause-and-effect relationships with words such as because and so in answers to questions such as –

Q: Why did the boy want to row his boat to the South Pole?

A: He wanted to row the boat (to the South Pole) because ________

- …he read that penguins come from the South Pole.

- …he couldn’t get the big ship to take it there.

- …he thought it was where the penguin wanted to be.

A: The boy wanted to row his boat to the South Pole so __________

- …he could return the penguin to its home.

- …the penguin wouldn’t feel sad anymore.

and so on.

More Grammar and syntax, Cause-and-effect relationships

On the next few page turns, see the boy and penguin on the high seas. The story says that –

There was lots of time for stories, and the penguin listened to every one, so the boy would always tell another.

To work on grammar and syntax, including complex sentence structures, talk about the boat going over the waves……

- ….while the boy tells stories.

- ….as the penguin listens to the boy’s stories.

- ….during a storm with thunder and lightning.

Express the story in a cause-and-effect relationship, such as –

- The penguin listened to all the boy’s stories, so ____________ (e.g., the boy kept on telling them).

Similes, Synonyms, Adjectives

To work on similes, synonyms, and adjectives, use the text

…waves were as big as mountains

to describe the wave pictured during the storm. Talk about how the word mountain is a good choice to describe how huge and tall the waves are. Encourage the use of the simile with adjectives and other words for big, such as –

- ….as huge as a mountain

- …as enormous as a mountain

More adjectives include gigantic, monstrous, colossal, and immense.

More Concepts of Print, Vocabulary

On the next page turn, the boy arrives at the South Pole where he helps the penguin out of the boat.

Welcome to the South Pole.

To work on vocabulary, continue to enhance the meanings of previously targeted words, shadows and reflections. Point them out and ask –

- What is the dark shape under the South Pole sign called? (shadow)

- What is the shape on the water beneath the boat called? (shadow)

- What is the light shape beneath the iceberg called? (reflection)

More Grammar and syntax

Observe how the boy helping the penguin out of the boat as you encourage storytelling from the illustration. Scaffold language constructions as you target specified grammar and syntax objectives, from two- and three-word utterances to more complex formations. Some suggestions –

- Penguin gets out (of boat).

- The boy pushes the penguin (up onto the ice).

- The boy helps the penguin get out (of the boat).

- The umbrella comes out (of the boat).

- The penguin first puts the umbrella on the ice.

- Icebergs float (on the water).

Drawing inferences, Predicting, Point of view

The turning point in the narrative comes on the next three page turns. The text reads –

Then the boy said good-bye…

… and floated away.

As the boy leaves and waves goodbye, he notices the penguin, standing on the ice bank, holding the umbrella he packed for their trip,

…looking sadder than ever.

To draw inferences about meaning from the words of the story, support children in expressing their realization about what the penguin may have wanted all along. Ask questions such as –

- Why do you think the penguin is “looking sadder than ever”?

- Did it like being with the boy in the boat?

- What might it have wanted all along?

Here the story offers an opportunity to address the concept of perspective-taking, both from the standpoint of one’s senses (e.g., visual perspective), and from a conceptual standpoint (i.e., understanding another’s thoughts, feelings, wants, and needs). The illustration shows the boy leaving in his boat from the visual standpoint of the penguin, who is left alone on the shore of the South Pole. Ask questions that help children see the story from the penguin’s perspective, such as

- What does the penguin see?

- What does the boy see?

- When the penguin sees the boy rowing away and waving his hand, how might it be feeling?

- If you were the penguin, how would you feel about the boy rowing away and waving goodbye?

On a page turn, point out the boy thinking through his decision to drop the penguin off at the South Pole and then take off. Now children see the story from the boy’s point of view. When he realizes this was a mistake, he also realizes that –

The penguin hadn’t been lost. It had just been lonely.

Ask questions about what his behaviors mean when we see the boy….

- scratching his head

- his hand on his chin

- opening his mouth and stretching out his hands

Scaffold answers to questions that enable children to express in their own words the boy’s realization and encourage predictions about what will happen next. Ask questions such as –

- What does the boy realize about his friend the penguin?

- What do you think he will do next?

On the next page turn, see the boy rowing back to the South Pole to get the penguin “as fast as he could”. But the penguin has already left in his “boat” (the upside down umbrella he’d offloaded first on arrival), and was on the other side of the iceberg. This is a great opportunity to work on the story’s point of view and perspective-taking, from both the visual and conceptual standpoints of the characters. Ask what’s happening with thoughtful questions such as –

- What had the penguin decided to do?

- What made the penguin leave his spot on the South Pole?

- Does the boy know he left? Why not?

- Can they see each other? Why not? (The penguin is on the opposite side of the iceberg from the boy, the boy is on the opposite side of the iceberg from the penguin, the boy can’t see around the iceberg, and so on.)

- Why can’t the boy see the penguin, even in his telescope?

On the next page turn, the boy sadly sets off rowing his boat back home when he spots a tiny spec in the distance.

- Could it be his friend?

As you turn the page to see what the boy saw, encourage children to express in their own words the sight of the penguin inside the umbrella, rowing it in the water to meet the boy.

See the wonderful embrace on the adjacent page. Encourage children to describe in words what happened and what the boy finally realized.

- Why did the boy think all along that the penguin was lost?

- After he took dropped him off and waved goodbye, what did he realize?

- After he turned his boat around to find him, was penguin found?

- What else was found?

Also note the penguin navigating the waters, inside the upside down umbrella, with an oar in hand. Encourage children to identify and describe the “vehicle” as you target multiple speech and language objectives with this heartwarming scene.

At the last page turn, see the boy and his new pal, the penguin, escorted by a pod of whales on their way home in the tiny rowboat, talking together at last.

Articulation

To work on phoneme production throughout the story experience, look for multiple opportunities to work on plosives P and B and the liquid glide L as the words appear in the text and illustrations.

Words containing P in the text: penguin, Pole (South), pushed, pass, point, disappointed, ship, help, sleep

More words in the illustrations: pushed (the penguin out of boat)

Words containing B in the text: boy, birds, big, boat, book, rowboat, bad, good-bye, back

More words in the illustrations: iceberg, umbrella

Words containing L in the text: lost, lonely, looked, help, sleep, pole, small, lots, listen, always, tell, float, until, finally, delighted, suddenly, telling, realized, last, sadly, closer

More words in the illustrations: pictures: whale, umbrella, lightening, land

After the read aloud, when children have had time to absorb the story, go back over the pages to review the illustrations and continue working on speech, language, and literacy objectives.

Vocabulary, Synonyms and Antonyms, Grammar and syntax

Review the title, Lost and Found, and provide opportunities for children to express its meaning.

To work on synonyms and antonyms, ask children to put the words lost and found into sentences as you target vocabulary development as well as grammar and syntax constructions, from early utterances to more Complex sentence formations. For example, ask –

- What’s the opposite of lost?

- What are some ways to use lost in a sentence about the story?

Some suggestions:

- The penguin was lost.

- The boy thought the penguin was lost.

- The boy lost the penguin after he took it back to the South Pole.

- The penguin thought he had lost the boy after he was dropped off at the South Pole.

- What’s the opposite of found?

Then ask children for ways to use found in a sentence about the story. Some suggestions –

- The boy found the penguin.

- The penguin lost the boy

- The boy lost a friend, but then he found him again.

- The penguin lost the boy, but then he found him again.

- The boy and penguin found each other and became friends.

Pragmatic language

To work on conversational skills as they relate to social pragmatic language, point out that the penguin does not talk throughout the story. Giving it dialogue would remove the mystery surrounding its appearance and the quandary the boy finds himself in. The penguin can’t tell him his needs, nor does the boy expect it.

After the story, however, children can imagine what the penguin and boy might say to each other on their return trip, as the story says –

So the boy and his friend

went home together, talking of

wonderful things all the way.

Consider supporting children in creating a dialogue between these two friends.

- What might the penguin want to tell the boy?

- What might the boy want to know?

- How might the friends reminisce about what they had experienced together?

- What might they tell each other about what they want to do when they arrive home?

- What stories about their prior adventures might they tell each other?

To work on the social pragmatics of being friends, talk about what contributed to the penguin and boy becoming close friends. Consider starting a discussion by asking –

- What things did they do that helped create the bond of friendship?

- In what ways did they enjoy each other’s companionship?

- How did the boy’s wanting to help the penguin create good feelings toward each other?

Some suggestions –

- The penguin participated in the boy’s plans.

- The penguin helped the boy pack for the trip.

- The penguin helped push the boat out to sea.

- The boy told stories in the boat “to help pass the time.”

- The penguin “listened to everyone.”

- The boy helped the penguin out of the boat.

- The penguin felt that the boy cared.

Discussion, Answering Why-questions

Once the child has a chance to absorb the story, discuss what the title, Lost and Found, has come to mean. Walk through the story’s events and ask questions such as –

- When the penguin arrived at the boy’s house, what did the boy think?

- Why did he think the penguin was lost?

- Why did the boy try to help the penguin find its home?

- When he left the penguin at the South Pole, what did the boy lose?

- When he went back to get the penguin, what did he find?

- When the boy dropped him off, did the penguin lose a friend?

- Did the penguin find the boy? What else did it find? (a friend)

Sequencing events

In reviewing the story, support children in identifying the boy’s attempts to solve the problem in sequential order, using connecting words first, next, then, after that, finally, and so on. For example,

- First he went to the Lost and Found Office.

- Next, he asked the birds in the park.

- Then he asked his bathtub ducky.

- Then he read his book about where penguins come from.

- After that, he tried to get a ship to take it back to the South Pole.

- Finally, he decided to take the penguin back home in his own rowboat.

Problem solving

Support children in identifying the problem in the story and then discuss the boy’s attempts at solving it.

- What was the problem in the story?

- What did the boy do about the penguin showing up at his door? (e.g., took it to the Lost and Found Office, asked the birds in the park, asked his rubber ducky, etc.)

- How did he feel then? (e.g., discouraged)

- Did his first attempts at solving the problem work? Why not?

- Did the boy’s problem get resolved?

- How did it get resolved?

- How would the story have been different if the boy hadn’t realized the penguin was not lost, but lonely?

- What would you have done if you were the boy?

- When the boy realized the penguin was not lost, did that solve the problem?

Storytelling

This is an ideal book to work on story schema due to the depiction of the characters’ emotions and boy’s attempts to solve what he believes to be the penguin’s problem.

Structure and scaffold children’s narratives that contain the following essential story grammar elements that make up a complete episode. Children should be able to understand and express the boy’s motivation toward his goal and how his feelings motivate his behavior. Ask questions about…..

- Characters: Who is the story about?

- Setting: Where does the story take place?

- Initiating Event: What happened to start the story off?

- Internal Response: How did the boy feel about this?

- External Attempts: What did the boy do? How did he respond to the situation?

- Consequences: What happened as a result of his attempts?

- Internal Response: When he finally got the penguin to the South Pole, how did he feel?

- External Attempt: What did that motivate him to do then?

- Outcome: How did the boy and penguin each feel about this and how did their relationship change?

Begin with the first few elements. Support children in putting them together in literate discourse style. Continue until a whole episode can be told with few prompts. If helpful, go back and review methods for problem solving to assist in expanding the narrative.

Executive Functioning

Because language drives the neural networking of executive functions, it can be helpful for children to verbalize strategies the characters put in place that lead to the story’s outcome. Working on strengthening these skills has the benefit of enhancing other literate discourse skills as well, including storytelling.

To work on planning, organization, initiation, and persistence, revisit the pages showing the boy’s attempts to help the penguin.

- What were the boy’s first steps in putting a plan in place to help the penguin?

- When none of those strategies worked, how did the boy persist in his goal? (e.g., went to his book for research that might lead to answers, etc.)

- When the boy decided to go to the South Pole, what plans did he put in place? (e.g., prepared the boat for sea, packed a suitcase, remembered an umbrella, and so on)

To work on flexibility, review the pages after he drops the penguin off at the South Pole and sets out to return home. The story reads –

There was no point telling stories now

because there was no one to listen

except the wind and the waves.

Instead, he just thought.

And the more he thought

…the more he realized he made a big mistake.

Talk about the boy’s realization and then re-thinking about what the penguin really wanted. How did he change his perception of the goal? Then ask children what is involved with flexible thinking. For example –

- Do you have to be able to change what you’re doing if your perception of the goal changes?

- How did the boy talk his way through realizing what the penguin really wanted?

- Did the boy then change his perception of what needed to be done?

- How might he have talked his way through needing to change direction?

Fluency

The minimal text and easily identifiable illustrations make this book a good resource for working on fluency techniques such as easy start, light contacts, and phonation on a steady breath stream. Throughout the story and afterward, consider having the child retell and sequence of events in a format that is familiar, enabling easier application of the target technique. For example,

- First the boy went to the Lost and Found.

- Then he went to the park to ask other birds.

In addition to fluency techniques, speech-language pathologists treat other aspects of this complex disorder to competently address components such as feelings, beliefs, behaviors, and rationales for change. The story of the penguin that does not speak provides interesting opportunities to work on avoidance, self-acceptance, openness, and self-disclosure as indicated for that unique child. Consider the following suggestions if they apply:

To work on adjusting attitudes and moving away from beliefs such as “I don’t have to change”, “I don’t need to speak” and “I can get others to speak for me”, consider holding a discussion (in an appropriate setting) on avoidance. While we know that penguins and other animals don’t talk, we typically suspend our disbelief in stories where animals do plenty of talking. But in this story, we are asked to realize that penguins really don’t talk (at least not until it is implied at the end that this one can), and we appreciate the boy’s dilemma as he tries to help his unexpected visitor. Possible questions to start a discussion include –

- Why was it hard for the boy to understand the penguin’s problem?

- How would the story have been different if the penguin had said, “I’d like to play with you” when he arrived at the boy’s house?

- Would it have mattered how he said it?

- How is avoiding speaking similar to the penguin’s silence in the story?

- Do others get a sense of why you may feel sad, for instance, when you avoid speaking?

- What is the difference between avoiding speaking and being unable to speak?

- What kinds of things can avoidance lead to?

- Is speaking to someone important, even though you might stutter?

To work on openness, use the events of the story as the boy thinks through how he left the penguin at the South Pole as a segue to self-awareness and problem solving. Talk about how the boy finally realizes what the penguin wanted. Because of his self-awareness and ability to think about his actions and the penguin’s response, he didn’t lose a meaningful friendship. He found friendship!

To be comfortable with one’s stuttering (or any speech disorder) is to develop self-awareness about one’s actions and acknowledge openly the difficulties it can bring to speaking. Encourage a belief that evaluating one’s actions, as the boy did in the story, is beneficial in all aspects of life. Stress that the importance of communicating lies in what you have to say, not how you say it. By avoiding speaking, you can leave others perplexed, like the boy in Lost and Found. But just as the story ends on a happy note with both of them going

…home together, talking of wonderful things all they way

we are reminded that communicating with others is well worth it!

_____ # # _____

NOTE: Find literally hundreds of picture books – including others by Oliver Jeffers – ideally suited for building the skills like the ones addressed here on Book Talk in the Skills Index of Books Are for Talking, Too! (Fourth Edition). See them cross-referenced to three age-related catalogs where you’ll find book entries that provide you with methods, prompts, word lists, activities, and loads of other ideas! These well-known, classic picture books are easily obtained through school and public libraries, and reasonably priced at online booksellers

PLUS! For a thematic approach to literature, find other books that cover this book’s topics and many more in the Topic Explorations Index of Books Are for Talking, Too! (4th Edition). Then see book treatments for those books in the catalogs where you’ll find methods, like those here on Book Talk, for building oral communication and early literacy skills.

~ All in One Resource! ~

Books Are For Talking, Too! ~ Now in its 4th Edition

~ Engaging children in the language of stories since 1990 ~

Special Note: Read about the 2024 news story of a penguin’s surprising arrival on a tourist beach in Australia, the interesting use of mirrors that helped him recover, and his wonderful release back into the ocean just 20 days later at:

Plus Activities! Here is a link for companion activities to Lost and Found. Very reasonably priced on Teachers Pay Teachers!