Book Talk

Supporting Children’s Speech, Language, and Literacy

Each year, an astonishing array of picture books enters a billion-dollar global children’s book industry. Books for children ages 4 through 8 make up a huge percentage of that market. It is easy to see why, given their creativity and entertainment value. Since its first publication in 1990, Books Are for Talking, Too! has placed a spotlight on special books for storybook read-aloud interactions. These are books I’ve found ideally suited to target specific areas of speech, language, and literacy development. Each book entered in the catalogs lists skills to target, ways to promote the skills during shared book reading, and more!

With so many impressive books on the shelves, I wish I had room to fill the pages with every book I’d love to share. As new books come onto the market, I find even more I want to present.

By showcasing a few here on Book Talk, I can share my ideas with you on how these great books can be used to engage children in developing oral communication and literacy. You may even think of more ideas. That’s great!

Along with publication information, you’ll find a summary that includes some of the book’s interesting features, such as the author, artist, topic, and related topics. Following that, you’ll see a Methods section with ways to use the book to develop the specified skills, all through the speech-language-and-literacy connection.

The elements I look for in these books are these: a quality story and illustrations, illustrations, and illustrations. Pictures that support a minimal text and tell a story in themselves, one the audience can connect with, capture the interest of the young (and not so young) – and you – the person who brings the story to life – the presenter.

Special Note: I try to select books that are readily available through school and local libraries, which means many are award-winners or notables to the extent they are widely recognized.

BOOKS ARE FOR TALKING, TOO! (4th Ed) is out now ON AMAZON.

Praise for Books Are for Talking, Too!

Great Resource for Parent Participation. I have been a Speech Pathologist for many years and one of the hardest aspects of the job is facilitating carryover with a home program. “Books Are for Talking, Too!” makes this simple. The book is already divided into sections for target skills of language, phonology, articulation, and pragmatics. Using grade level, you look under the desired subject, and you can provide parents books that correlate to the goals being addressed. Nothing to purchase, these books are classics, award winning literature found in our public libraries that kids and parents can enjoy together while reinforcing communication!

Incredible Resource! I purchased this book for my Special Education Preschool team to use during their professional development meetings. I’ve since received many thank you’s for providing such an excellent resource! They’ve used it in collaborative planning sessions to address goals in language development and early literacy, and report that they continue to refer to the book time and time again…. I highly recommend this valuable resource!

Great for parents, teachers, and speech therapists… The book has easy to follow suggestions that anyone can use. Well-known children’s books can be used to help a child’s speech, language, and overall learning. I’m a Speech Pathologist and have used earlier editions of this book. So glad this newer one has landed.

Books Are for Talking Too! is a very useful resource for those who want to target specific reading and language skills. It can also help homeschooling parents select children’s books based on themes such as seasons, pets, and music, or select books simply by reading the helpful synopses.

My go-to for therapy planning!

Books Are for Talking, Too!”, now in its fourth edition, is a Must-Buy! ….One of the book’s strengths is its focus on inclusivity and diverse learners, providing guidance on adapting techniques to accommodate children with special needs or those from bilingual or multilingual families. In summary, “Books Are for Talking, Too!” is a valuable resource for fostering a lifelong love of reading and learning in children.

As a speech-language pathologist I love to refer to this book….because I can look up a direct treatment plan for specific skills to meet the needs of the children I treat. Many great ideas!

I love that popular children’s books are featured throughout with fun, clear read-aloud activities for targeting various speech and language skills.

[Ms.] Gebers emphasizes nurturing a child’s curiosity and offers actionable tips easily implemented by both professionals and parents.

Excellent book for planning literacy sessions.

Book Selection for September

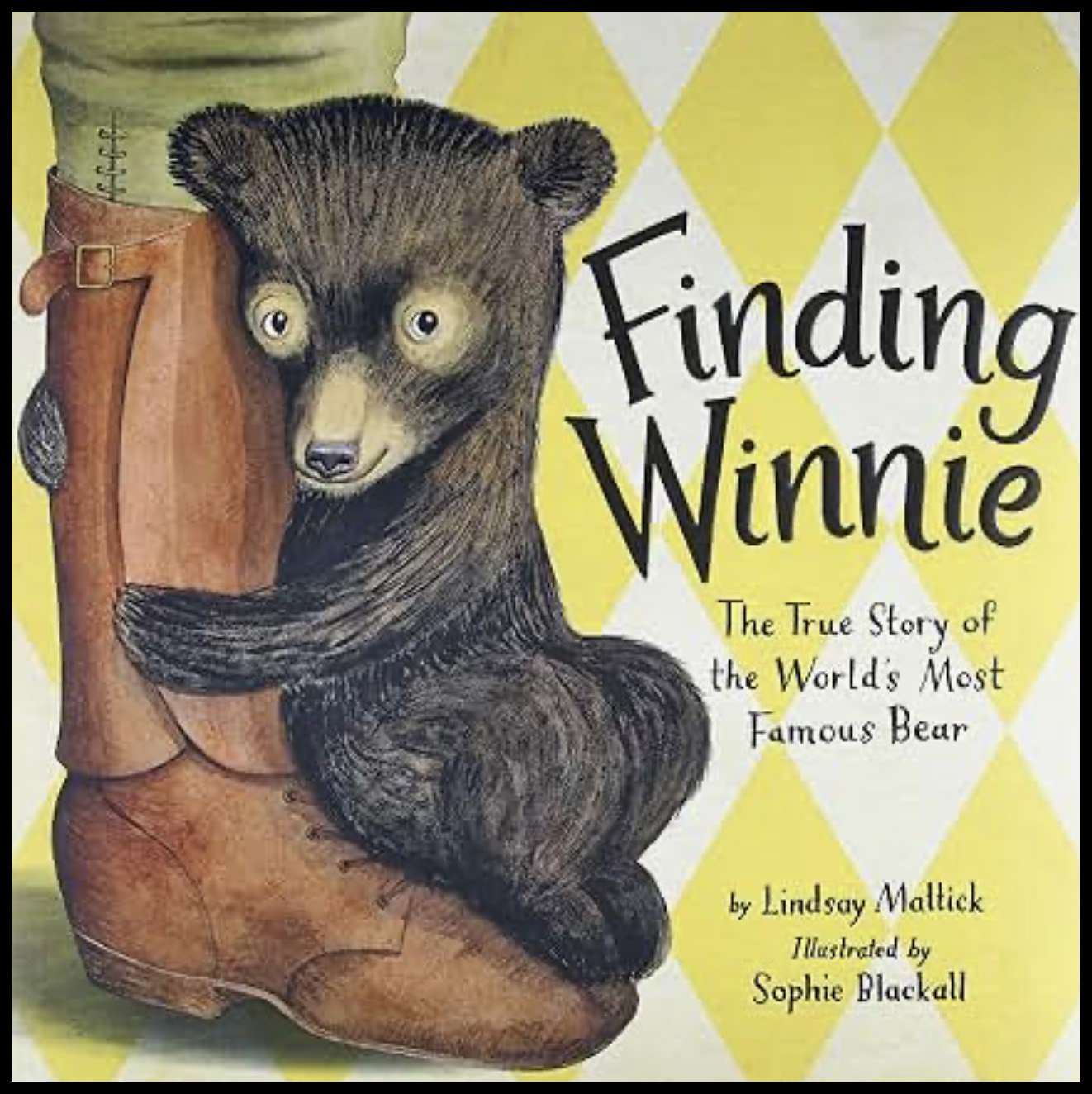

Finding Winnie: The True Story of the World’s Most Famous Bear

by Lindsay Mattick, Illustrated by Sophie Blackall

When I think about how effectively a picture book can engage even the most reluctant participant at story time, I know that one quality has to stand out – its ability to relate to the child. Does it make sense? Is the cover intriguing? Does it make you feel something? Do you – and the child – want to know more?

One glance at the cover of Finding Winnie and we are entranced. What could be more intriguing than a small bear hugging the boot of a soldier? Does a child recognize a baby bear? The booted leg and foot of a human? The warmth of an embrace? The answer to all of these is probably, yes!

Few know the true story behind the classic character, Winnie-the-Pooh. Surprisingly, A.A. Milne did not fashion Winnie from his imagination. The author tells the story of her great, great grandfather, a veterinarian during WWI, who rescued a cub, named it after his hometown of Winnipeg, and brought it with the troops traveling through Canada, and across the Atlantic Ocean where they would be stationed in England. Couple this amazing story with award-winning Sophie Blackhall’s artistic rendering of events and characters’ feelings and you have an absolute winner!

There are a multitude of skills waiting to be supported as you pause for book talk within the pages of this loving story. Encourage early utterances, improve vocabulary, and scaffold a myriad of language constructions. You’ll find a complete narrative structure ideal for teaching storytelling skills. The planning, preparation and goal attainment of the main character are also ideal to highlight in support of various executive functions.

By using the treatment plan that follows, you can save time analyzing the book for its possibilities and easily accomplish a variety communication and literacy objectives all at once. Because of this, I consider it to be another one of Book Talk’s powerhouse picture books.

Please Note: Powerhouse picture books have a lot to offer! The following book treatment is extensive in order to cover the many skills this resource can be used to address.

You likely will not use all the methods listed. Consider first scanning for skills you most want to target. Then check out the full treatment to see others. Getting to know the book’s possibilities may lead you to think of even more!

Tip: Also, please know that any of these skill-building methods can be introduced after the book is shared, when you return to revisit the pages. For some learners, too many expected responses may be counterproductive.

In these cases, know that it’s OK to ask yes/no questions and even provide the answers during your initial read-aloud. Sensitivity to the child’s ability level and present state of mind is always advised. Going back to review the story once the child has absorbed the material can be just as productive and rewarding.

The most important thing is that you create an enjoyable experience with the child, the story, and you, the presenter.

SO, LET’S GO!

Finding Winnie: The True Story of the World’s Most Famous Bear

by Lindsay Mattick, Illustrated by Sophie Blackall

Boston: Little, Brown Books for Young Readers, 2015.

Suggested age and interest level: Pre-K through 3

Editions: Hardcover, Paperback, eBook, Audiobook

Languages: English, Chinese, German. Italian, Japanese, Korean, Persian, Spanish

Awards and mentions: Caldecott Medal Winner, 2016, #1 New York Times Bestseller, and a whole string of others

Topics to Explore: Bears, Teddy Bears; Family; History; Journeys; Kindness and Empathy; Zoos

Skills to Build:

Concepts of Print

Semantics: Vocabulary, Homonyms, Synonyms, Attributes, Idioms, Metaphors (figurative language), Prepositions

Morphological units (suffixes)

Grammar and syntax: Two- and three-word utterances, Noun + verb agreement, Tense structures (present progressive, past, future, and advanced syntax structures)

Language literacy (a.k.a. Language discourse): Relating personal experiences,Sequencing events, Cause-and-effect relationships, Predictions, Problem solving, Drawing inferences, Answering Why questions, Storytelling, Discussion

Executive functions: Goal selection, Planning and organization; Initiation and persistence, Flexibility, Execution and goal attainment, and Regulation

Fluency

Articulation: Phonemes K and H

Summary: This is the remarkable true story of the real bear that inspired A. A. Milne’s classic children’s book, Winnie-the-Pooh. Lindsay Mattick tells the story of her veterinarian great, great grandfather’s encounter with a little cub tied to a bench at a Winnipeg train station. Despite traveling with his regiment during a time of war, Harry Colebourn followed his heart and bought the bear from the trapper, rescuing her from an unknown fate. He named her Winnie, after his hometown of Winnipeg, and she joined the troops as they embarked on their long journey to prepare for war.

From the fields of Canada to a famous convoy across the Atlantic to an army base in England, the little bear delighted the soldiers as they prepared for battle. But battlegrounds would not be a safe place for Winnie, so Harry again followed his heart and drove her to the London Zoo where she could be taken care of. That was where Winnie made another new friend, a real boy named Christopher Robin.

The back material includes WWI-era photographs and diaries of Colebourn, the man who followed his heart, and amazing photos of Christopher Robin right next to Winnie inside her zoo enclosure. The child’s father published a children’s story about this extraordinary friendship in 1926, immortalizing the incredible bear and forever warming our hearts.

Methods:

Before the read-aloud, show the cover and share that the book tells the incredible true story about an exceptional little bear, named Winnie. And she was a girl!

Concepts of print,

Relating personal experiences,

Making predictions

To help younger children develop print awareness, read the title and subtitle as you run your finger under the words in the direction in which they are read. Explain that the letters represent talk written down, and the words inside the book will tell the story, along with the pictures.

To work on relating personal experiences, ask children what they know about Winnie-the-Pooh. Consider sharing a copy of A. A. Milne’s classic book or a picture of Winnie-the-Pooh from the internet.

If children have experience with the stories, encourage them to relate what they know about this classic teddy bear.

To work on predicting events, ask children to describe what they like best about the cover illustration. Then ask –

- What’s unusual about this picture?

- Where is the bear cub?

- What do you think this story is going to be about?

During the read-aloud, model, scaffold, expand, and recast targeted language structures while using the illustrations and text in the following ways:

Two- and three-word utterances,

Present progressive tense structures,

Prepositions

On the title page, reread the tile and subtitle.

To work on two- and three-word utterances, talk about the little bear in the tree looking across at the bunny to elicit picture descriptions such as –

- little bear * little bunny

- bear in tree * bunny on path

- bear sees bunny

To work on present tense constructions and prepositions, expand utterances to include where the action in taking place, i.e.,

- up in the tree

- on the path

- across the meadow, and so on.

Present tense structures,

Relating personal experiences

On a page turn, the story opens with a child named Cole requesting his mother tell him a story before bed. Pause to restate how the story begins and what the boy is holding, as in-

- Cole wants a bedtime story.

- Cole is holding his teddy bear

Also encourage children to relate their own experiences at bedtime.

- Do you have a special stuffed animal?

- Do you like a story at bedtime?

- Tell about your special animal.

Vocabulary, Attributes

On a page turn, see the illustration of the man petting the horse. The text reveals the setting that begins the story, including the character, Harry.

Pause before the page turn to talk about the word veterinarian.

To work on attributes, discuss what made Harry a good veterinarian. He was –

- kind

- caring

- warm

Talk about the setting in Winnipeg, Canada, where the country is typical of the flat plains called tall grass prairie and winters were very cold.

Past and future tenses

On a page turn, see Harry at the train station boarding a train to go off to war.

To work on past tense constructions, pause to talk about the wars of history where soldiers mounted horses. Discuss the horses’ need for good care. Encourage sentence constructions in past tense to retell the story, such as –

- The horses needed care.

- The veterinarians tended to the horses.

To work on future tense constructions, talk about what Harry was going to do, or would do, on his arrival.

- Harry would take care of the horses.

- The horses would need a veterinarian.

Two- and three-word utterances,

Prepositions, Idioms

On a page turn, see the train move through beautiful snow-covered mountains until it reaches the station. The text reads –

The train rolled right through dinner and over the sunset and around ten o’clock and into a nap and out the next day, until it stopped at a place called White River.

To work on early utterances, encourage repetition of parts of the text as it relates to the beautiful images.

To work on prepositions, talk about the implication of time that the text implies and discuss the images in terms of wherethe train went, as in –

- on the train tracks

- over the bridge

- inside tunnels

- through the mountains

After the train rolls into the station, the text states –

Harry decided to stretch his legs.

To work on idioms, talk about how sone words put together are called an expression, and can have a different meaning than that of their individual words. In this case, to stretch your legs means to go for a short walk after sitting in one place for a long time.

Then scaffold children’s attempts to use it in a sentence. For example,

- Harry was sitting on the train for so long he needed to stretch his legs.

- I need to stretch my legs after I sit for too long.

Vocabulary, Drawing inferences,

Metaphors (figurative language)

On the next two page turns, we meet the charming baby bear. As the mother tells the story to her son Cole, see the little cub tied to a bench by a trapper.

Discuss the meanings of words trapper and cub.

To work on drawing inferences, discuss the meaning of the text,

“that Bear has lost its mother,” he thought, “and that man must be the trapper who got her.”

Ask –

- Why would a little cub be at a train station?

- Why does the trapper have the cub tied to the bench?

- What must have happened to the cub’s mother?

Then see Harry, the veterinarian, struggle with a decision. The story reads –

Then his heart made up his mind…

To work on metaphors, or figures of speech, talk about the meaning of the words. Ask –

- What does it mean when your heart makes up your mind?

Point out the picture of Harry walking in circles, scratching his head. How is Harry feeling? Talk about how difficult making choices can sometimes be.

Talk about how kindness and empathy can shape our opinions and the choices we make.

Homonyms, Vocabulary,

Syntax (present and past tense constructions),

Metaphors (figurative language), Making predictions

On the next five page turns, see how the little cub joins the troops of the Canadian Army, how the officers welcome her into their regiment, name her Winnie, care for her, and even train her! Winnie was in the Army now!

To work on homonyms, show the page where Winnie is safely on Harry’s lap, being fed and learning to drink on her own from a baby bottle. The text says –

The men roared.

Talk about the different meanings of the word roared, as in –

- A wild animal’s deep, loud sound, like that of a lion

- To move at a high speed, making a constant sound, as a car roars down the road

- To laugh loudly

To work on vocabulary, show the text stating that Winnie was a good navigator. Ask for definitions in the event your audience has prior knowledge. Then explain that a navigator is crucial to the success of a regiment to ensure safe and accurate travel routes

The illustration shows Winnie clinging to the trunk of a tree, certainly giving her a better perspective than her fellow army men. Ask –

- In what ways might she have been a good navigator?

- She was small, but did she have an advantage over the officers?

To work on syntax formations, ask children to tell what Winnie is doing, or did, in order to relate the story in past tense. Point out her path taken around the tents to find a hidden object, even if it was far away.

To work on metaphors, or figures of speech, point out that when thinking about their pending trip across the Atlantic Ocean, Harry again had doubts about taking Winnie along. The text reads –

His head said, “I can’t.” But his heart made up his mind.

Talk again about the meaning of the words. Ask –

- What does that mean when your heart makes up your mind?

- How can kindness and empathy form our opinions and choices we make?

To work on predicting events, ask children what they think will happen next, based on the story’s events so far.

N + V agreement,

Regular and irregular past tense constructions

On the next page turn, see the setting where their journey begins across the Atlantic. Discuss the huge warships –

carrying about 36,000 men, and about 7,500 horses…and one bear named Winnie.

Point out the little cub riding on the bow of the huge ship.

To work on N + V agreement, model, shape, expand, and recast descriptive sentences about the ships and the little bear, such as –

- The ship heads out to sea.

- The ships head out to sea.

- The bear rides on the ship.

- The horses ride on the ships.

- The ship and Winnie leave the harbor.

- Many ships leave the harbor

To work on regular and irregular past tense constructions, encourage sentence constructions using the verbs sail and ride.

- Lots of men sailed on the ships.

- Lots of horses sailed on the ships.

- Winnie sailed on a ship.

- Lots of men rode on the ships.

- Lots of horses rode on the ships.

- Winnie rode on a ship.

Vocabulary,

Syntax (Present progressive and Complex constructions),

Metaphors (figurative language),

Making predictions

On the next three page turns, see the cub accompanying the Second Canadian Infantry Brigade at their training in England. The men wholeheartedly embrace her presence in their regiment, calling her their mascot. Winnie was in the Army now!

To work on vocabulary, discuss the meaning of mascot (e.i., a person, animal, or object that symbolizes an organization and thought to bring them good luck).

Give examples from baseball, such as –

- The Pittsburgh Pirates have the Pirate Parrot.

- The Arizona Diamondbacks have Baxter the Bobcat.

- Chicago Cubs have Clark the Cub.

To work on syntax formations, use the illustrations of the soldiers and Winnie to describe what they are doing, such as marching in the rain, living in tents, and getting their picture taken with Winnie.

Support children’s advanced syntactic structures with consistent phrase expanders, such as –

- When Harry was in the Army, he _______ (e.g., tended the horses, kept care of Winnie, marched with the soldiers, etc.).

- When Winnie was in the Army, she ______ (exercised, lived in a tent, had her picture taken, and so on.)

But Winnie is growing bigger. When the order comes for the men to go to battle, Harry thinks seriously about what to do with Winnie. The text reads –

But his heart made up his mind.

To work on metaphors, discuss again the figurative use of the text. Ask –

- What do you think that means?

- Was he making a hard decision?

- How did he finally decide?

To work on making predictions, ask children what they think will happen next.

- Will Harry take Winnie along with the soldiers into the battlefield?

- Will Harry think about what’s best for a little bear cub?

Early utterances,

Answering Why questions, Problem solving

On the next two page turns, see Harry drive Winnie to the city where he takes her to her new home at the London Zoo.

Notice the topography of the rolling hills with hedgerows and Stonehenge in the background as they drive the car to the London Zoo.

To work on early utterances, use the illustration of Harry and Winnie in the car to encourage repetition of portions of the text, as in

- Harry drove

- Big city

- Winnie and Harry

- They drive together.

Then see their emotional farewell. Harry tells Winnie there is something she must always remember.

Even if we’re apart. I’ll always love you. You’ll always be my bear.

Encourage children to construct meaning from the page to tell what is happening in the scene.

To work on answering Why questions, ask why Harry took Winnie to the zoo. Model, scaffold, expand, and recast children’s responses to express their understanding, such as –

- The soldiers were going to battle.

- The war front was not a good place for Winnie to be.

- Winnie would be safe at the zoo.

To work on problem solving, ask children to state the problem and solution. Support the construction of responses such as –

- The problem was that going to war with soldiers wouldn’t be good for a bear.

- Harry solved the problem by taking Winnie to live at the zoo.

- Harry decided to put Winnie in a place where she was safe

Drawing inferences,

Cause-and-effect relationships

On the next three page turns, the story transitions to a different place and time, and we see different characters. Discuss the transition.

A little boy with a teddy bear can’t think of a suitable name for his stuffed animal. When his father takes him to the zoo, he sees a bear in a big enclosure and becomes friends with her. Her name is Winnie.

When he comes home he names his teddy, Winnie-the-Pooh! His father wrote books about his son, Christopher Robin, and his friend, Winnie-the-Pooh, named for the bear of the Second Canadian Infantry Brigade saved by a veterinarian, Harry.

To work on drawing inferences, ask children to explain who the bear is that the boy sees in the zoo.

To work on cause-and-effect relationships, ask children what effect the boy’s visit to the zoo has on his teddy bear. For example –

- How did the boy’s teddy bear get the name Winnie-the-Pooh?

Encourage the use of connector words so and because in responses. For example –

- The teddy was named Winnie-the-Pooh because the boy met Winnie, the real bear, at the zoo.

- The boy finally named his teddy bear because he met the real bear, Winnie.

- He liked the bear at the zoo, so he named his teddy bear after her.

Metaphors (figurative language)

On the next two page turns, the story transitions back to Harry, the veterinarian, as he comes back from the war and visits Winnie at the zoo.

The story tells that Harry went back to Winnipeg, married, and had a son. His son grew up and had a daughter, and that daughter had a daughter named Lindsay. Lindsay is Cole’s mom, telling Cole the story of his great, great grandfather and his decisions from his heart that led to heartwarming stories for generations to come.

To work on metaphors, point out the illustration with the progression of family members. Talk about the meaning of a family tree. Explain that a family tree helps us visualize people’s ancestry, with each branch representing the descendants.

After the read-aloud, visit the back material to see photos from the family album. They include war-time photos of a real live Winnie with Harry Colebourn, and then right next to the little boy, Chrisopher Robin, at the London Zoo. Point out Harry’s diary from the year, 1914 and other fascinating details. Ask children to share their thoughts, such as –

- What are your favorite photos of Winnie?

- What makes these photos so interesting?

- What does seeing the photos make you feel about this story?

Then review the pages to work on additional skills such as –

Synonyms, Morphological units (suffixes)

The story tells us that Winnie was a “Remarkable Bear.” Talk about the meaning of remarkable, as in worthy of being or likely to be noticed, especially as being uncommon or extraordinary.

Brainstorm synonyms for remarkable, such as

- Extraordinary

- Outstanding

- Notable

- Uncommon

Talk about the parts of the word by breaking it down into its syllables.

- Re – mark – a – ble

To work on morphological endings, show how adding the suffix –able to the word remark makes remarkable.

Demonstrate how the suffix works with other synonyms, as in –

- Not – able

- Ador – able

- Love – able

Then encourage use of the words within the context of the story, such as –

- Winnie was a notable bear.

- She was an adorable cub.

- The officers in Harry’s troop found that Winnie was a loveable bear.

Then brainstorm more words with suffix –able, such as –

- Readable

- Breakable

- Washable

- Dependable

Encourage use of the brainstormed words within the context of everyday life, as in –

- The letters are readable.

- The glass is breakable.

- My sweater is washable.

Sequencing events

Review the pages to talk about the journey the little bear took with the Canadian soldiers as they traveled across the Atlantic Ocean to their post in England.

Encourage language discourse with connector words, first, then, later, next, and finally. It might go something like this –

- First Harry traveled on a train through the mountains with his troops.

- Then they stopped at a train station where Harry saw the cub.

- Then he bought the cub, and they traveled by train to a camp in “the green fields of Valcartier.”

- Later, they made the voyage with a convoy of ships across the ocean.

- Next, they set up camp in England, on the Salisbury Plain.

- Finally, Harry drove Winnie to the London Zoo where she was loved and cared for.

Storytelling

Finding Winnie is ideal for working on story schema due to its depiction of the setting, characters’ emotions, Harry’s attempts to solve the problem, and the extraordinary outcome.

Structure and scaffold children’s narratives that contain the following essential story grammar elements to make up a complete episode. Children should be able to understand and express Harry’s motivation toward his goal and how his feelings motivate his behavior. Ask questions about –

- Characters: Who is the story about?

- Setting: When and where does the story take place?

- Initiating Event: What happened to start the story off?

- Internal Response: How did Harry feel about this?

- External Attempts: What did Harry do? How did he respond to the situation?

- Consequences: What happened as a result of his attempts?

- Internal Response: When he finally got the cub to the London Zoo, how did he feel about this?

- External Attempt: What did that motivate him to do then?

- Outcome: How did Harry and cub each feel about this? How did their relationship change? Did Harry do the right thing in his kindness toward the cub? What events happened as a result of this?

Begin with the first few elements. Support children in putting them together in literate discourse style. Continue until a whole episode can be told. If helpful, go back and review methods for sequencing events and problem solving to assist in expanding the narrative.

Discussion

Return to the title page and read the dedication –

To Cole. May this story always remind you of the impact one, small loving gesture can have.

Throughout the story, the Army needed to move toward its destination, the battlefield. This meant Harry had to make decisions about the well-being of the little cub. Ask –

How did Harry make his decision ____

- …at the train station?

- …at the Canadian camp in Valcartier?

- …when training for war on England’s Salisbury Plain?

Each time, the story tells us

…his heart made up his mind.

Talk about Harry’s choices. Ask children for their thoughts.

- Did Harry do the right thing?

- What makes you think so?

Executive functions

The story is true! And let’s face it. Life in the Army is different. Harry and his troops had to adjust their daily lives and plan to accommodate their little friend for life among the soldiers. This included crossing the ocean on board ship for a long journey!

Harry also had to be flexible and think about the best decisions for Winnie as well as his troops. Discuss the following aspects of this extraordinary endeavor. Many are things children may need to consider in caring for their own pet.

- Goal Selection: The story shows how Harry walked in circles thinking about whether to buy the cub and bring her with him. Ask –

- What might have been on Harry’s mind before he made his decision?

Suggestions include –

- What should I do if I bring Winnie with us on our journey?

- Should I just use the old routine and hope Winnie makes it?

- Or, do I need to develop a plan?

2. Planning and Organization: The story shows Winnie was well received among the troops. But now what? Harry would surely have been thinking about how to plan for her new life so different from the natural forest where she was from. Ask –

- If you were Harry, what would you do?

- What would you talk about with your fellow troops?

- What would you be asking yourself once you brought Winnie to the Army?

Suggestions include –

- How do I determine what a little cub needs in the Army?

- Do we need special things for her?

- Do we need a strategy? A plan?

3. Initiation and Persistence: The story shows that the troops brought in plenty of food for Winnie. The text reads –

They brought her carrots and potatoes, and apples and tomatoes, and eggs and

beans and bread. And a tin of fish, and some slop in a dish. But Winnie was still

hungry.

Harry knew that a little bear’s needs are constant. When he needed to be somewhere else, how could he make sure she was safe and didn’t destroy their camp? Ask –

- If you were Harry, what would you do?

- How should you initiate the plan? First with self-talk?

- Should you write it down, or talk it out, even with your regiment?

Suggestions include –

- Write down a plan, make a chart, and talk out loud about it.

- Assign each man a job, like getting the food.

- Flexibility: The story tells that –

Harry taught her to stand up straight and hold her head high and turn this way

and that, just so! Soon she was assigned her own post.

Winnie learned to do lots of things, but that wasn’t by leaving her on her own. Ask –

- Why did Winnie need to be taught to do special things? Like commands?

- If you were Harry, would you need to be flexible?

- What would you have to change and plan for when Winnie boarded a ship?

Suggestions include –

- Make sure Winnie is trained so she could be managed by the troops.

- Make sure Winnie is looked after by someone when Harry has work to do.

- Make sure they could change the plan in a different situation, like on a ship (like bringing plenty of food for her to eat!).

- Execution and Goal Attainment relies on flexibility and self-evaluation. The story says that winter had arrived and –

The time had come to fight.

In thinking about the real goal for Winnie, what does that mean in terms of her welfare? Ask –

- Will Harry have to evaluate the situation and be able change his mind?

- Will Harry have to make a new plan if conditions aren’t safe for Winnie?

- Did rescuing Winnie mean keeping her with him no matter what?

- Or, did it mean keeping her safe and well so she would have a good life?

Suggestions –

- Winnie needed to be safe.

- Winnie couldn’t go back into the wild because she couldn’t fend for herself.

- Winnie needed to be taken care of by people who loved her just like the troops.

- Regulation: Once Winnie was transferred to the zoo, Harry needed to evaluate his decision to make sure it was a good one. The story tells us

When Harry visited Winnie at the zoo, he saw how happy she was. She was being raised. She was truly loved. And that was all he had ever wanted from the moment they met….

Ask –

- How did Harry judge whether his decision was right to take Winnie to London Zoo and avoid the battlefield?

- Did he need to alter his efforts? Or, did his ultimate goal succeed?

Then talk about how good planning and strategies lead to good outcomes – and in this story, for more than just Winnie!

Fluency

To practice fluency techniques such as easy start and initiating phonation on a steady stream of air, begin demonstrating with the character’s name, Harry, beginning with phoneme /h/.

Then review the pages and create short phrases or sentences about what Harry, initiating air flow before moving toward the word Harry as demonstrated. For example –

- …Harry rode the train.

- …Harry saw a cub.

- …Harry bought the cub.

Next, demonstrate the techniques of air flow followed by lip rounding, using the phoneme /w/ and the word Winnie.Structure responses of increasing word length such as –

- …Winnie ate lots of food.

- …Winnie slept by Harry’s cot.

- …Winnie had his picture taken with the soldiers.

To work on adjusting attitudes and moving away from beliefs such as “I don’t have to change”, “I don’t need to speak” and “I can get others to speak for me”, consider holding a discussion on decision-making.

Possible questions to start a discussion might include –

- How did Harry make his decisions about the little cub? Were they easy?

- How would the story have been different if Harry had given in to his fears about taking Winnie with him? What if he had not followed his heart?

Consider discussing the decision-making aspects of avoidance.

- How is avoiding speaking a decision?

- Is speaking to another important, even though you might stutter?

Other messages in this story may also be suitable for working on resilience and promoting healthy perceptions, depending on the unique child.

Articulation, phonemes K and H

To work on production of K, use the word cub to talk about Winnie and structure responses at the child’s ability level as you engage in Book Talk about the story through the text and illustrations.

Other words with K in the text and illustrations: Cole, Colebourn, Captain, Colonel, creature, Canada, camp, car, mascot, pictures, and like.

To work on production of H, use the name of the main character, Harry, when structuring responses to the literature as you demonstrate using a steady airstream before phonation of the complete word.

©SoundingYourBest.com/book-talk/

_______ # # _______

Note: Find literally hundreds of quality picture books ideally suited for building the skills addressed here in Book Talk – and a whole lot more – under the headings in the Skills Index of Books Are for Talking, Too (Fourth Edition).

Then find the book titles cross-referenced in three age-related Catalogs and discover similar book treatments that provide you with methods, prompts, and loads of ideas!

Plus! You’ll also find popular picture books that cover this book’s topics, including Bears, Family, Kindness and Empathy, and more in the Topic Explorations Index of Books Are for Talking, Too! (4th Edition). Then see them featured in the Catalogs with methods for supporting communication skills – for a lifetime of success!

All in One Resource!

Books Are for Talking, Too! (Fourth Edition)

~ Engaging children in the language of stories since 1990 ~

Available on Amazon at: https://a.co/d/efcKFw6

Extended Activities: Watch a video of the author, Lindsay Mattick, talking about her experience writing the book. You’ll see charming illustrations of Winnie-the-Pooh and hear her talk about the importance of adults sharing their stories with their children – and of children’s awareness about these stories so that they may ask questions about their backgrounds and know where they came from.

Some of the most amazing stories are true!

Visit: https://youtu.be/jfj9ZkD0dN8?si=ZTsePlHpZjuYofkv

Also! Watch the wonderful read-aloud video, Symphonic Storytime Finding Winnie: the true story of the world’s most famous bear accompanied by Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 5 in C-Sharp Minor, by CoosBayLibrary.org.

Then see a Listening Guide a the end with questions such as, What instruments do you hear? What instruments stand out? What do you feel while listening to the music? The suggestion is to leave this on while children color and create pictures of their own. Very inspiring!

Book Selection for August

The Man Who Didn’t Like Animals

by Deborah Underwood

Now we finally know the backstory of Old MacDonald’s farm! You see, it all started with this man who didn’t like animals. Really! And it says so right on the cover of this book!

Kids will delight in engaging in Book Talk with this story, as even the youngest can repeat the short lines of text and imitate the sounds of the happy farm animals .

A pig playing Scrabble, a goat reading a book (as it eats the pages), and a dog knitting a sweater while relaxing in its host’s favorite armchair are just a few of the eye popping events transpiring inside this man’s once tidy townhouse.

The book has it all – humor, repetitive sequences, a text that supports the illustrations, and illustrations that tell more than the text.

Much of the story can be “read” through the character’s body language. Award winning artist LeUyen Pham portrays the man who loves his tidy house with hilarious expressions and gestures that are easily interpreted and invite plenty of descriptions.

In addition to working on nonverbal communication and addressing the theme of friendship, it’s a great book for sequencing events and other literate discourse skills such as cause-and-effect relationships and problem solving, as well as addressing concepts of print and engaging in phonological awareness activities, to name just a few!

By using the treatment plan that follows, you can save time analyzing the book for its possibilities and easily accomplish a variety communication and literacy objectives all at once. Because of this, I consider The Man Who Didn’t Like Animals to be another one of Book Talk’s powerhouse picture books.

Please Note: Powerhouse picture books have a lot to offer! The following book treatment is extensive in order to cover the many skills this resource can be used to address.

You likely will not use all the methods listed. Consider first scanning for skills you most want to target. Then check out the full treatment to see others. Getting to know the book’s possibilities may lead you to think of even more!

Tip: Also, please know that any of these skill-building methods can be introduced after the book is shared, when you return to revisit the pages. For some learners, too many expected responses may be counterproductive.

In these cases, know that it’s OK to ask yes/no questions and even provide the answers during your initial read-aloud. Sensitivity to the child’s ability level and present state of mind is always advised. Going back to review the story once the child has absorbed the material can be just as productive and rewarding.

The most important thing is that you create an enjoyable experience with the child, the story, and you, the presenter.

SO, LET’S GO!

The Man Who Didn’t Like Animals

by Deborah Underwood

New York: Clarion Books, an imprint of HarperCollins, 2024.

Awards: A New York Times/New York Public Library Best Illustrated Children’s Book of the Year 2024; Amazon Top 20 Books of the Year 2024.

Topics to Explore: Animals, City Life, Communities, Friendship, Perspective-taking, Sounds and Listening

Skills to Build:

Concepts of Print

Semantics: Vocabulary, Metaphors, Categories, Prepositions

Morphology (prefixes)

Grammar and syntax: Two- and three–word utterances, Present progressive and past tense structures, Advanced syntax structures, Negative structures

Language literacy (a.k.a. Language discourse): Making predictions, Sequencing events, Cause-and-effect relationships, Problem solving, Drawing inferences, Point of View, Answering Why questions, Discussion

Pragmatic social language: Nonverbal communication, Being a friend

Articulation: K and G, L

Phonological Awareness

Summary: A fun read-aloud about a tidy man who lives alone in the city. He doesn’t like cats. Enter a cat. Then another. He doesn’t like dogs. Enter a dog. Then another. He doesn’t like ducks, chickens, pigs, goats, or any other animals, but they all find their way to the man who doesn’t like animals and crowd his once tidy home, making their unique sounds. Strangely enough, he finds shared interests with all his new companions and begins to enjoy them. But when “cranky” neighbors come, he must decide. Part with all the animals he now loves? Or (spoiler alert), move to a farm! EE-I-EE-I -O!

Methods:

Before the read-aloud, introduce the book and share the cover, where a story is waiting to be told! Support literacy and spoken language development by engaging children in the following ways –

Concepts of Print, Making Predictions,

Pragmatic language (Interpreting gestures and expressions)

To work on concepts of print, show the cover and read the title, The Man Who Didn’t Like Animals, running your finger under the words in the direction in which they are read.

The additional text at the top reads –

Before there was Old MacDonald, there was …

You may wish to ask children what they know about Old MacDonald and his farm – or you may wish to leave out the reference to the well-known character as it certainly has a spoiler effect.

To work on making predictions, ask your audience to describe what’s going on. Point to the man leaning out the window scratching his head as he looks at a cat on the windowsill. Talk about all the animals gathered around the steps of the entrance. Reread the title and ask –

- How could this be?

- How could it be that a man who doesn’t like animals lives where there are lots of them around?

- Do you think he’s aware of the other animals at the side of the steps?

Encourage predictions of what the story will be about.

- Do you think the man likes all the animals beside his house?

- What do you think the animals are going to do?

- What will the man do about all those animals?

To work on interpreting gestures and expressions, talk about the man as he looks at the cat.

- What is he doing? (Scratching his head)

- What might he be thinking? (How did a cat get on my windowsill? How am I going to get rid of this cat?)

- What does his expression tell us? Does he like the cat?

Concepts of Print, Vocabulary. Categories,

Social Pragmatics (Nonverbal communication),

Syntax structures, Prepositions

During the read-aloud, pause at the inside cover for Book Talk as you follow the man through his village street.

To work on concepts of print, point out the signs that label each of the stores along the street where the man is walking. Read them aloud, running your finger under the word in the direction the print is read. They include the –

- Fromagerie (cheese shop)

- Hardware store

- Sports store

- Bird Shoppe

- Reptile House

- Book store

- Music store

- News kiosk with pinned posters

To work on vocabulary, name the items in the picture, such as the –

- Horse

- Buggy

- Fence (enclosing dog park)

- Birdcage (carried by woman)

- Potted plant (carried by the man)

Encourage use of the word, linking it to other words within the context of the story. Model, scaffold, and expand on child responses.

To work on categories, ask children to name all the animals on the street scene, many of which are hanging out of upstairs windows. They include –

horse, dog, goose, lizard, pig, cat, cows, and donkey.

Then ask –

- What are they all called? (animals)

Note: See the additional Categories heading listed below in the section, After the read-aloud.

To work on nonverbal communication, point out the man’s reaction to the animals as he sees them on the street.

The title says the man doesn’t like animals. Talk about what his expressions and body language say about how he is feeling. Ask –

- Why is he turning his head to look behind him as he leaves the reptile house?

- Why is he looking away with his arm outstretched toward the horse?

- Why is he holding his plant in the opposite direction as he looks at the cat?

Now locate the man playing with the dogs in the dog park. Talk about how he is communicating something different. Ask –

- How are his actions and gestures different from those of the man?

Answers include –

- He smiles.

- He is facing the dogs.

- His hands are outstretched toward the dogs.

To work on present progressive tense, prepositional phrases, and advanced syntax structures, continue talking about the action in the story using various verbs to construct present tense sentences, including walking, carrying, eating, talking, driving, and looking.

Then expand the simple sentence with an adverbial phrase to explain where the action is taking place. For example –

- The man is walking ____

…down the street

…across the street

…in the middle of the street

…past the shops

…in front of the horse

…away from the horse

…toward home

Follow the man down the road to tell what else he is doing and how he feels about all the animals he encounters.

Syntax structures, Social Pragmatics (Nonverbal communication)

At the title page, read the title again and continue to share in the telling of the story as you follow the man with the plant up the stairs to his home.

To work on present progressive and past tense structures, ask questions such as –

- After the man went shopping, then what did he do?

- What’s happening in the story now?

To work on nonverbal communication, point out and identify the man’s reaction to the woman’s dog passing by on the sidewalk. Ask –

- What do his expressions and gestures say about how he is feeling?

- What doesn’t he like now?

- How can you tell?

Vocabulary, Social Pragmatics (Nonverbal communication)

On a page turn, the first page of story text reads –

There once was a man

who loved his tidy home

and who didn’t like animals.

Discuss the word tidy and ask for definitions, such as –

- neat

- no clutter

- well arranged

- everything in its place

Then ask for examples from the illustration, as in –

- What are some things in the picture that tell us he has a tidy home?

Answers can include –

- He has a duster.

- He’s wearing an apron.

- There is no clutter, or mess.

Then use the words in connection with other words on the page to create sentences about the story.

To work on nonverbal communication, point out and identify the man’s expression while cleaning his house, and how it is now different.

- Has his expression changed?

- How does he feel now?

- What does that say about what he likes?

Social Pragmatics (Nonverbal communication),

Two- and three-word utterances, Negative syntax structures

On a page turn, read the text that describes what happens to start the story off.

One day, a cat appeared.

To continue work on nonverbal communication, share talk describing how the man uses gestures and expressions to try to communicate with the little cat. For example, ask –

- How is the man trying to communicate with the cat?

- What do his gestures say?

- What is he saying when he _______

…puts his hands on his hips and turns his mouth down?

…lifts his hands up high and wiggles his fingers toward the cat?

…pulls his hands up high when the cat rubs against his legs?

Then talk about the importance of our gestures and expressions when we communicate with others. Ask. –

- How do our own gestures talk?

Give and share examples.

To work on early utterances and syntax structures, encourage repetition of the short text. Then ask what the man is saying so children can use the words in a way that relates the events of the story. Shape structures into negative formations, as in –

- The cat did not go away.

- The cat did not leave the house.

Two- and three-word utterances, Syntax constructions

On a page turn, see the man realize all the things he and the cat have in common.

To work on two- and three-word utterances, encourage repetition of the words of the text as you point to the pictured action, such as –

- …sleeping in the sun

- …watching the rain

- …eating dinner

To work on present tense constructions, model, scaffold, and expand responses about the man and cat with verb phrases. For example, say –

- They are _______.

…sleeping by the window (in the sun).

…walking outside in the rain (together).

…watching the rain.

You can also begin a sentence for the child to repeat and then complete. Begin by asking –

Q: What do they both like?

A: They both like _________(e.g., sleeping in the sun, walking the rain, eating dinner together).

Negative syntax structures, Predictions,

Social Pragmatics (Nonverbal communication)

On a page turn, see another cat appear at the man’s door.

To work on negative syntax structures, encourage children to repeat the text, filling in the last word, as in –

- I don’t like cats.

Then use language that tells the story, as in –

- He doesn’t like cats.

To work on predictions, ask children what they think will happen next and express the reasons for their predictions. For example –

- Do you think the cat will leave?

- What makes you think it (will or won’t)?

To continue syntax formations, pause to encourage picture descriptions and talk about the second cat sleeping on man’s head!

*Note: Also point out the cat bowls with the printed names that will continue to grow in number as the story unfolds. Ask children how the animals came to have names.

To work on nonverbal communication, continue to identify the man’s expressions and body language as he points to the door in a gesture indicating the cat must leave. Then discuss how the man’s expression changes. Since the story doesn’t relate their dialogue, encourage children to provide the “talk” for what the characters are saying as you share in the process of Book Talk.

Predictions, Negative and present tense syntax formations

On the next five page turns, see a dog, another dog, a duck, more ducks, a chicken, and more chickens enter the once tidy home. Each time they do, the man says, “Go away.” But with each animal that arrives, the man finds steadfast friendship.

Continue to work on language skills as you’ve done on the previous pages by describing the activities the man and his growing number of animal friends like to share. The repetitive structure is predictable, enabling the child to participate with consistency that’s so beneficial in reinforcing skills.

Negative and present tense syntax formations,

On a new page turn, see the house from a new perspective as it is filled with animals popping out of the windows, all making their special sounds. Pick out the different actions taking place to support the skills you want to target as you share in Book Talk. Also support the use of different verb phrases.

Cause-and-effect relationships, Problem solving

On a page turn, see the “cranky” neighbors arrive at the house. Pick out more details that add to the chaos in this scene, including –

- pigs playing Scrabble

- the dog knitting

- ducks swimming in a barrel

- the pig playing the piano

- the hen in a next on top of the piano

and so forth.

To work on cause-and-effect relationships, ask children what caused the neighbors to get so upset. For example, ask –

- What effect did all the animals have on the neighbors?

Support constructions with connector words such as so and because, such as –

- The neighbors got mad because the animals were making too much noise.

- The animals were making too much noise, so the neighbors came to complain.

Or, provide the first part of the sentence and have the child complete it starting with the connector word.

To begin work on problem solving, ask children to state the problem in the story, as in –

- The neighbors don’t like the noise.

- There are too many animals living in the house.

- The situation is out of control!

Then ask for ideas about how the man should solve the problem.

Problem solving, Point of View, Answering Why questions.

On a page turn, see the man thinking through his dilemma and telling the animals –

“I’m sorry, but you’ll have to go,” he said.

To continue working on problem solving, ask what the man did to solve the problem. Answers may include –

- He thought about it.

- He agreed the animals made a lot of noise.

- He made a decision.

To work on point of view and perspective-taking, point out how the man agreed with his neighbors that the animals were making too much noise. Ask –

- Was that usual or unusual?

- Was that a bad choice or a good choice?

Talk about how the man understood his neighbor’s point of view.

To work on answering Why questions, ask why the man sent all the animals away, even though he was enjoying them. Model, shape, and expand on utterances using connector words so, so that, and because.

Metaphors, Drawing Inferences, Concepts of Print

On a page turn, see the man heartbroken, then changing his mind as he runs after the animals calling,

WAIT!

To work on concepts of print, identify the letters of the names printed on the pet food bowls. Then show the word wait on the opposite page, in the talk bubble. Explain how it represents the man’s talk written down.

To work on metaphors, talk about the meaning of a broken heart. Often called a figure of speech, the words used in this context indicate loss, grief and sadness. Ask –

- What does his expression say about how he truly feels about the animals?

To work on drawing inferences, ask how we come to realize he changed his mind, even though it isn’t stated.

Concepts of Print, Problem solving, Syntax construction

On the remaining page turns, see the magnificent hug, the cleanup and departure from his home, and the joyous ride as they relocate to Old MacDonald’s Farm and live happily ever after. Sum up the story with a comment such as –

- So, now you know the origins of Old MacDonald’s Farm, just like the book cover states!

To continue work on concepts of print, show that the sounds the animals make have changed from the oinks, moos, and baas to aaahhhhs once they all reunite.Also show how the newly arrived farmer paints his sign with letters that say Old MacDonald’s Farm, and that the animals are now learning their letters, EE-I-EE-I-O!

To finish working of problem solving, talk about how the man who didn’t like animals finally solved his problem by bringing all the animals he now loves to live with him on a farm.

To continue work on syntax construction, encourage talk about what’s happening in the illustrations as the happy crowd works together to build their happy life on the farm.

Articulation, phonemes K and G, and L

The text is heavily loaded with the repeating velar plosives K and G, and the liquid consonant L. Throughout the story, work at the child’s acquired ability level to produce the accurate sound(s) during Book Talk.

To work on K and G, use the opportunity of the repetition of the word cat and go (away) in the beginning pages.

Additional words with K in all positions in the text: car, like, taking, walks, came, duck, ducks, chicken, chickens, cow, cows, cranky, called, cluck, and oink.

Words with K in the illustrations: park, couch, clock, kitty, cane, clean, and chorus.

Words with G in all positions in the text: gardening, pig, goats, gathered, grew, grass, dog, and began.

Words with L in the text and illustrations: plant, like, love, table, animals, sleep, cluck, ladder, street light, slowly, called and filed.

After the read-aloud, ask children to tell you their thoughts about the story. For example, ask –

- What was your favorite part/page?

- What did you like most about it?

- Why was that an important part of the story to you?

Then review the pages to work on additional skills such as –

Discussion

Hold a discussion on friendship. Ask children how it was that a man who didn’t like animals came to love them. Ask what happens when you share activities with a special someone. How does your friendship grow?

Sequencing Events

To work on sequencing events, ask children to describe the picture sequence of the animals that came to visit the man in his house, culminating with the arrival of the “cranky” neighbors. Scaffold with connecting words first, then, next, and finally. For example –

- First, a cat arrives.

- Then another cat arrives.

- Next, a dog arrives.

- Then another dog arrives.

- And then a duck, chickens (and so forth) .

- Finally, the “cranky” neighbors arrive to complain.

Categories

To work on categories, review all the animals in the story and ask what kind of animals they are (farm animals). Continue to group items in the story into categories by asking –

- Name all the types of furniture in the man’s house.

- Name all the activities the man and animals liked doing.

- Name all the rooms in the house that the animals were in.

- Name all the cleaning utensils the man used.

Go back to review the illustrations if needed. Then connect the category word with other words in the story to create sentences, such as –

- The animals sat on the furniture.

- The man and his animal friends liked to do activities together.

- The animals were in all the rooms of the house, even the bathroom.

Social Pragmatics (Being a friend)

To work on using language effectively in social contexts, including making friends, finding commonality and enjoying things that you each have in common, asking questions such as –

- What are some good ways of making friends?

- What are some ways that the man and his animal visitors became friends?

- What did they enjoy doing together?

- What kinds of things could they have said to each other when doing the things they enjoyed?

Morphology – prefixes

In this story, the man starts out not liking animals. He doesn’t like animals. Or you can say he dislikes animals.

Use the animals in the story to create sentences about what the man dislikes.

- He dislikes cats.

- He dislikes dogs.

- He dislikes ducks.

and so on.

Share other words that start with the prefix dis-. Explain that the prefix frequently means to do the opposite of when used in front of the root word. For example,

- Dis – connect

- Dis – continue

- Dis – agree

- Dis – appear

- Dis – assemble

- Dis – belief

- Dis – cover

- Dis – infect

- Dis – obey

Discuss the root words. Give examples of their meaning or ask children to define the words and use them in a sentence.

Then say the word with the prefix. Show how the new word is the opposite of the root word. Then use the new word in a sentence.

Phonological Awareness

Play Phonological Awareness (PA) games with the words of the text.

Note: If the child’s abilities fall on the earlier end of the PA spectrum, you may want to start with the games provided here at the Initial Sound Awareness level.

If the child has been assessed at the advanced Phonemic Awareness levels, consider working on other activities for Phoneme Analysis and Phoneme Manipulation, to name a few. Given the short amount of text in the story, creating a list from this source may need to be supplemented with other story-related words. Then proceed with specified activities that focus on each level of the continuum until the child has achieved the final stages of phonemic awareness

NOTICE: ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. The following phonological awareness games are copyrighted material from the 3rd and 4th editions of Books Are for Talking, Too! They are the intellectual property of the author/publisher. They are used here in Book Talk by the author/publisher for educational purposes only. Duplication of this material for commercial use is prohibited without explicit permission from the author/publisher.

Initial Sound Awareness Level – Alliteration

Please Note: In all the following games, “the sound L” or “the sound P“, etc., means the phoneme, and should be produced as the sound, not the letter name.

Play: Same-Sound. Children identify whether two words (or three-word strings) from the text begin with the same sound. For example,

say –

- Listen to the following words: love, like.

- Do the words love and like start with same sound? (Yes)

- Yes, love and like both start with the sound L.

Continue using words from the following list. Intersperse non-alliterative words into the sets to make odd pairs:

- love, like

- like, ladder

- cow, cat

- man, meow

- cluck, clock

- bath, bark

- goat, go

- tidy, table

- dog, duck

- pig, piano

- chair, chickens

- farm, food

- neighbor, noisy

Now play Same Sound with 3-word strings. For example,

say –

- Listen to the following words: like, love, ladder.

- Do the words like, love, and ladder start with the same sound? (Yes)

- Yes, like, love, and ladder all start with the sound L.

- Listen to the following words: man, meow, bark.

- Do the words man, meow, and bark start with the same sound? (No)

- No. Man and meow start with the sound M. Bark starts with the sound B.

Intersperse non-alliterative words into the following 3-word strings:

- love, like, ladder

- man, meow, move

- bath, bark, baa

- cat, cow, car

- dog, duck, dish

- goat, go, game

- farm. food, fingers

- pig, piano, park

- neighbor, noisy, neat

Odd-One-Out. Children select from a string of alliterative words the one that does not belong based on its beginning sound. Use the list provided in the Same-Sound game to build word strings with a non-alliterative word. For example,

say –

- Listen to the following words.

- Which word does not start with the same sound as the others?

- dog, duck, oink (oink)

- That’s right. Oink is the odd one out.

Word-Search. Children search for a word in an illustration or recall a word from the text that begins with the same sound as a target sound or target word. For example,

From the opening scene of the man dusting in his living room, say –

- I’m searching for something in this picture that starts with the P sound.

- Can you help me find a word that begins with P? (e.g., piano.)

Or say –

- I’m searching for a word that starts with the same sound as cat.

- Can you help me find a word? (e.g., couch )

Say-the-Sound. Children listen to a series of words taken from the text and produce the initial sound common to each word. For example,

say –

- Listen to the following words: park, piano, pig.

- What sound do they all start with?

- That’s right! Park, piano, and pig all start with the sound P.

Continue by using the alliterative word strings provided in the Same Sound game.

Note: For book treatments that encompass the full range of phonological awareness (PA) skills, check out the Phonological Awareness Catalog in Books Are for Talking, Too! (Fourth Edition.) You’ll get tables showing the hierarchy in the development of PA, and a whole range of activities and instructions to use with easy-to-find picture books.

© SoundingYourBest.com. All rights reserved.

_____ # # _____

Note: Find literally hundreds of quality picture books ideally suited for building skills addressed here in Book Talk – and a whole lot more – in the Skills Index of Books Are for Talking, Too (Fourth Edition). Then find the book titles cross-referenced in three age-related Catalogs and discover similar book treatments that provide you with methods, prompts, word lists, activities, and loads of ideas!

Plus! You’ll find other popular picture books that cover this book’s topics, including Farm Animals, City Life, Communities, Friendship, Sounds and Listening, and more in the Topic Explorations Index of Books Are for Talking, Too! (Fourth Edition). Then find the books featured in the Catalogs to support you in using a thematic approach to literature – building skills for a lifetime of success!

All in One Resource!

Books Are for Talking, Too! (Fourth Edition)

~ Engaging children in the language of stories since 1990 ~

Available on Amazon at: https://a.co/d/efcKFw6

Extended Activities:

Great, must-see Read-Aloud of child reading this book! YouTube: “Kids Read Aloud – The Man Who Didn’t Like Animals” – https://youtu.be/R9WwrplKTJw?si=T04CQLfBZDKt2oOG

Book Selection for July

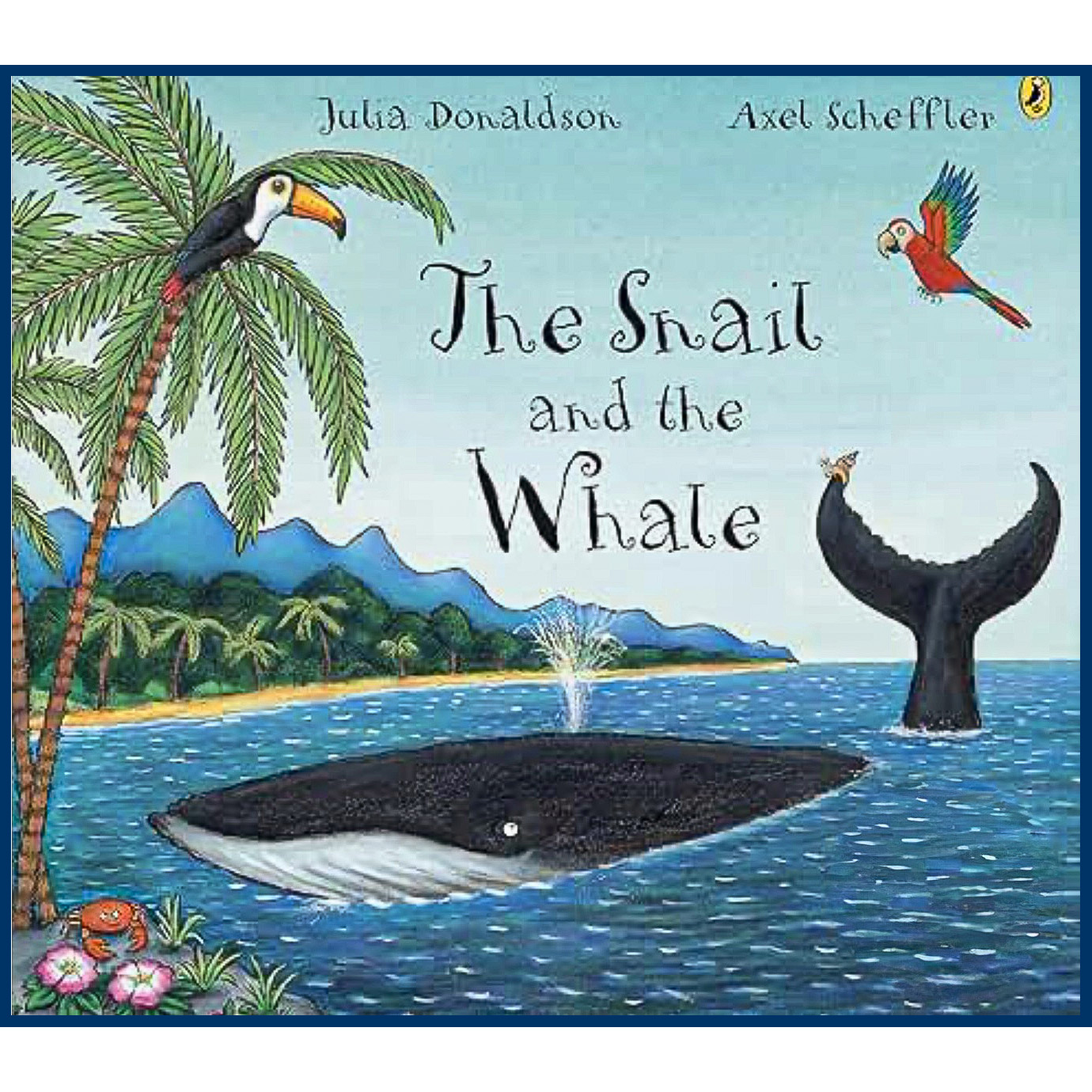

The Snail and the Whale

by Julia Donaldson, illus. Alex Scheffler

A tale of kindness! Renowned English author Julia Donaldson’s rich use of rhyming verse in a story with a fairly repetitive narrative structure provides a trove of opportunities for working on multiple skills. Just as importantly, her storytelling delivers a touching tale – charming, current, and relevant. It’s one that is sure to engage children’s curiosity, imagination, and participation.

I love that the author has stated it is one of her favorites, as its influence came from her childhood experiences listening to the poems of Edward Lear (i.e. “The Owl and the Pussycat”).

Its themes of friendship, courage, and belief in oneself can be applied to any skill you may be working on. It’s an excellent book to teach concepts of print, as the tiny snail cleverly creates loops and curls with her snail trail, transforming it into script to communicate her message. The author’s word choices, good use of verbs and adjectives, creates opportunities for developing vocabulary and syntax structures. Words from the rhyming text are ideal for phonological awareness activities, All of it is great material for quality Book Talk.

With so much potential to offer support in so many domains of communication and literacy, you can easily extend the activities throughout the month as you build skills and connect them to even more skills. Be sure to check out the additional digital resources for extended activities at the end of the book treatment.

By using the treatment plan that follows, you can save time analyzing the book for its many possibilities and easily accomplish a variety of speech, language, and literacy objectives all at once. Because of this, I consider The Snail and the Whale to be another one of Book Talk’s powerhouse picture books.

Please Note: Powerhouse picture books have a lot to offer! The following book treatment is extensive in order to cover the many skills this resource can be used to address.

You likely will not use all the methods listed. Consider first checking out the list of Skills to Build and scanning the treatment for those you most want to target. Then check out the full plan to see other ideas. Getting to know the book’s possibilities may lead you to think of even more!

Tip: Also, please know that any of these skill-building methods can be introduced after the book is shared, when you return to revisit the pages. For some learners, too many expected responses may be counterproductive.

In those cases, know that it’s OK to ask yes/no questions and even provide the answers during your initial read-aloud. Sensitivity to the child’s ability level and present state of mind is always advised. Going back to review the story once the child has absorbed the material can be just as productive and rewarding.

The most important thing is that you create an enjoyable experience with the child, the story, and you, the presenter.

SO, LET’S GO!

The Snail and the Whale

by Julia Donaldson

New York: Puffin Books, 2003.

Suggested age and interest level: Ages 3 to 7 years

Editions: Hardcover, Paperback, eBook, Large Print, Braille, and Magnetic Book. Also an Audio book available on iTunes.

Languages: English, Arabic, Chinese, German, Italian, Russian, and Turkish

Awards: Winner, 2004 Spoken Book gold award for best audiobook for ages 6 and under.

Topics to Explore: Animal rescue, Beaches and seashore, Friendship, Geography, Ocean creatures and habitats, Whales

Strategies for Book Talk: Consider pausing only minimally during the read-aloud so that the brilliant use of language crafted in rhythm and rhyme isn’t interrupted. However, pausing for children’s input and to define a word are always suggested. On a second read-though, target more specified skills you want to support.

Skills to Build:

Concepts of Print

Semantics: Vocabulary, Beginning Concepts (Part-Whole Relationships), Homonyms, Synonyms, Associations, Adjectives, Attributes, Prepositions

Grammar and syntax: Two- and 3-word utterances, Noun + Verb agreement, Singular and Plural forms of nouns, Syntax structures (past, present and advanced)

Language literacy (a.k.a. Language discourse): Relating personal experiences, Sequencing events, Cause-and-effect relationships, Predictions, Problem solving, Drawing inferences, Verbal expression (Giving explanations), Compare and contrast, Answering Why questions, Discussion

Pragmatic social language: Nonverbal communication, Being a friend

Fluency

Articulation, W, F and V

Phonological Awareness

Summary: A tiny snail with an “itchy foot” on a soot-filled rock overlooking a busy harbor has a wonderful dream. So, she advertises for a ride around the world. Her dreams come true when, after writing an ad with her silvery snail trail, she is invited to climb aboard the tail of a humpback whale. What a wonderful whale to take her to far off lands, to the South Pole’s icebergs with penguins and seals, and tropical islands with monkeys, palm trees, and spewing volcanoes. But when the whale gets pushed too close to land, he gets beached on an empty shore. Find out how the tiny snail saves the day with her courage and ingenious snail trail that rounds up the community. Together they all try to preserve the giant sea mammal until the tide comes in again and he’s heading back to port. Waiting for them is whole “flock on the rock” and they all climb aboard for a new adventure to end this endearing tale.

Before the read-aloud, encourage children to share what they know about the cover illustration, engaging in Book Talk as you support the following skills:

Vocabulary, Attributes, Discussion, Relating personal experiences

As you read the words of the title and author on the cover, encourage descriptions of the story’s setting, identifying the toucan perched on a palm tree, and parrot flying over the sea.

To work on vocabulary, talk about the whale and how it inhales air when it comes to the surface of the water using a blowhole, distinguishing it from fish. Describe how the whale blows a powerful burst of air from its blowhole, and that condensation from colder air outside creates the mist, making it look as if it is spewing water. After it has exhaled, then it inhales air and can swim under the water with this air until it is time to come back up again and repeat the process.

Name other attributes of this marine mammal, like its size, color, and special dorsal fin on his back (not visible in this illustration) that identifies him as a humpback. Then identify the tiny creature, barely seen at the tip of his tail – the snail.

As you discuss snails and their features, talk about how they leave a silvery, glistening snail trail behind them when they are on the move. This helps them navigate and propel their movement over rough, dry surfaces.

The snail trail is key to understanding the story. Ask children to relate their own experiences observing snails. Ask –

- Where did you see the snail?

- What do you notice about the snail?

- Have you ever seen a snail trail but no snail?

- What does its trail tell you?

Talk about the difference between a sea snail (like the one in the story) and a garden snail. For example, garden snails have lungs and sea snails have gills, so they can breathe under water.

During the read-aloud, model, scaffold, expand on, and recast language as you engage in children in Book Talk. Consider minimal interruptions in the flow of the rhyming verse on the first read-through, then pause for lengthier exchanges when you revisit the pages after the entire book has been read.

Perspective-taking, Vocabulary, Syntax structures, Idioms, Homonyms

On the first page turn, pause for talk about the setting.

To work on perspective-taking, point out the single tiny snail on the rock overlooking the harbor. Make the story come alive by asking –

- What can the snail see from the rock?

- How is her view different from those on the little boat coming into the harbor?

- How is it different from that of the seagull perched on top of the old pilings?

Vocabulary includes –

- Port

- Dock

- Cranes

- Tugboat

- Ships

- Anchor

- Seagulls

- Lichens (on rocks)

- Lighthouse

- Shore

- Buoy

- Metal barrels (oil drums)

- Pilings (providing a habitat for marine life)

To work on vocabulary and syntax formations, model use of the words in sentences and connect them to other words. Then scaffold and/or expand the child’s constructions, such as –

- Big ships are docked in the harbor.

- Cranes lift cargo (off the ships).

- Lichen grows on the rocks (and pilings).

- The seagull eats lichen (off the rock).

and so on.

To work on idioms and homonyms, talk about the expression itchy foot that is so important to the meaning of the story. Share that the expression means longing to travel or do something different. Ask yes/no questions to insure understanding. For example, ask –

- Does this expression mean the snail’s foot itches and she needs to scratch it?

- Does it mean she is itching to travel and see the world?

- Does the little snail long to set foot on other lands?

Share that a snail’s underside is called a foot. Which gives the idiom a homonym aspect. What does foot mean when referring to a sea snail?

Concepts of print, Idioms

On a page turn, see lots of snails on the soot-covered rock in the harbor. Talk about the shells on their back. Point out and run your finger along the snail trail as you read the text –

- This is the trail

- Of the tiny snail,

- A silvery trail that looped and curled

- And said, “Ride wanted around the world.”

To work on concepts of print, show the rock on which the snail created a message with her silvery trail. Talk about how she formed the loopy lines of her snail trail into letters – perfect for handwriting. Explain how the loopy letters say something in writing. They are talk written down. Ask –

- What did the snail want to say to the ships’ captains?

- What did she want to ask them?

- How was this clever?

Encourage children to be on the lookout for another place in the story where they might see the snail use her trail to write a message.

To work on idioms, talk about the meaning of the words, hitch a ride, as in getting a ride from someone for free, especially since they’re going where you want to go. They are especially important words to the meaning of the story.

Encourage use of the idiom, both within the context of the story and within children’s own lives.

Part-Whole relationships, Prepositions